A Take of Top 100 Global Multi-National Corporations (Source: Forbes 2014)

Post World-War II saw the large-scale expansion of the American multi-national corporation, so much so that hundreds of thousands of British jobs became dependent upon the phenomenon. In those early days it was not just about rampant wealth accumulation, most importantly there was a positive culture where employees felt an extension of family, a kind of corporate community spirit and a sense of genuine pride.

So offices were large and expenses not worried about so much, everybody did part of one job, unlike the comparative four jobs that people seem to do today. People wrote not emails but memos, the internal post department was huge, such memos were typed and sent in triplicate (sometimes more). People filed things and retrieved things from files. A lot.

The economic troubles of the 1970s (perhaps largely caused by a 1973 global oil price shock, which had nothing to do with UK government policy) saw rampant inflation and the rise of the UK Trades Union movement, a movement whose role was to represent the best interests of (mainly) government sector employees through the principles of collective bargaining.

What we may later have considered an original QUANGO (QUasi-Autonomous Non-Governmental Organization), called ACAS (Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service), was always very busy! It was an age remembered for endless strikes as wages failed to keep pace in the impossible race with inflation. By 1978 an inevitable recession had hit and hit very hard.

The American multi-national corporation did not recognize UK Trades Unions but instead invented a separate department to verify their legal, and to an extent moral, responsibilities. The Amercian-ised version of Personnel, became the universal Human Resources.

The challenge for this department was that labour law in America (hire and fire) was the opposite to parts of Europe (France or Germany) and different again from Britain. Further expansion through Asia plus emerging markets in Africa and Latin America saw the significant need for growth of this function. HR departments were not just global or regional but necessarily local, too.

From a UK legal perspective a company makes a role redundant, not a person. If a staff member is being let go and replaced in the same role, then either they have moved on within the company of their own volition, or they have resigned, or they have been managed out of the company on competency or performance grounds.

To do the latter requires a lot of process, time and effort. The employee needs to be aware they are being reviewed for performance or competency and have regular milestone meetings to measure and mutually agree their documented progress.

Let’s say it takes a middle manager of 8-10 staff, while also contributing their own value-added role, about 18 months to properly assess the contribution and performance of each team member. In the matrix-like structure of interdependencies that naturally makes up corporate life, the actual contribution of the individual is hard to quantifiably measure and assess.

The net result is that following and managing the process properly is a real headache for the manager, to the point where they may have the conversation that starts “You may be happier working in a different role in the organization.”

The employee then moves sideways into a different role with a new manager, a manager who in 18 months time will likely move them along again. By this rationale you might have a 10 years career in a corporation, having worked in 5 different roles and not been competent in a single one!

SME (Small to Medium Enterprise): Source: savings-banks.com

The SME (small to medium enterprise) is a different animal. Let’s say a firm that turns over less than £10m. There’s no hiding place. Staff contribution is measurable and visible by the hour. Nearly all staff will likely be on first name terms with the MD or CEO, who in turn know exactly what each staff member brings to the party. The tricky thing is that they certainly cannot afford the luxury of a £50k-£60k full-time Human Resources professional to tell them how to manage the turnover of their staff.

This is where things get a little tough; an SME does not have the size, scope nor slack to facilitate any number of staff not adding enough value in any particular role, moving sideways over time in their business. However, the rules about letting go of staff remain the same for these companies as they do for corporations. What do they do? Well, this scenario applies to full-time PAYE employment contracts, what alternatives exist?

Let’s consider top end restaurants, specifically those that do not belong to larger groups and those that turnover between £3m and £10m. Their cost base relates to their property and use of resources at the site; the cost of the ingredients on a plate, the cost of the cellar, but most of all it is the cost of their staff. Restaurants (and hotels) are labour intensive. They have big front of house, big back of house. Many staff would work long and sometimes unsociable hours. At the same time staff performance coupled with managed wage cost is crucial to the success of the business.

As a result employment contracts and shift patterns are different. How do they adjust to seasonality of demand for their product? How would you officially performance manage the career of a chef or a waiter? Or how would you move them on?

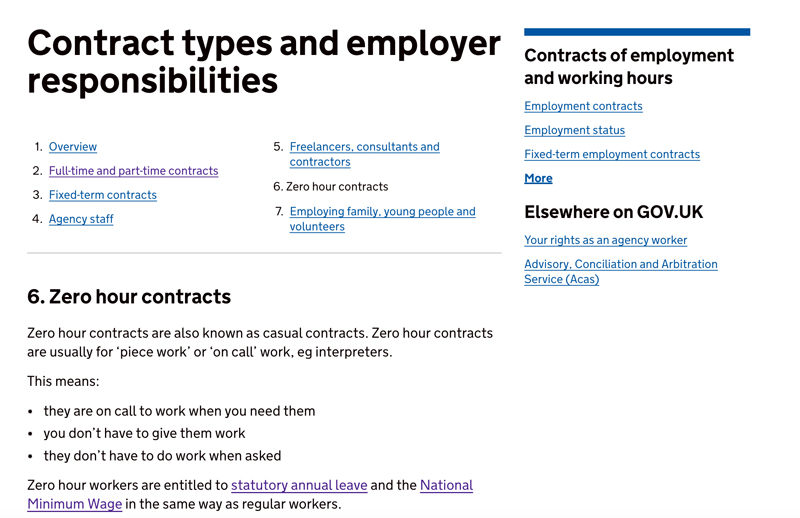

In essence, Zero Hours Contracts allow companies to hire and let go of staff as they wish. The stipulations are that the employee has a right to the National Minimum Wage and may seek alternative employment at any time without notice. The employer can take up their services as required but the employee has a right to refuse to work, although mutually agreed supplementary terms could be signed up to by both parties, for example stipulating a minimum of available hours work. These contracts have proven emotive and controversial as they have been argued to be exploitative of the workforce, while on the other hand offering flexibility to both employer and employee.

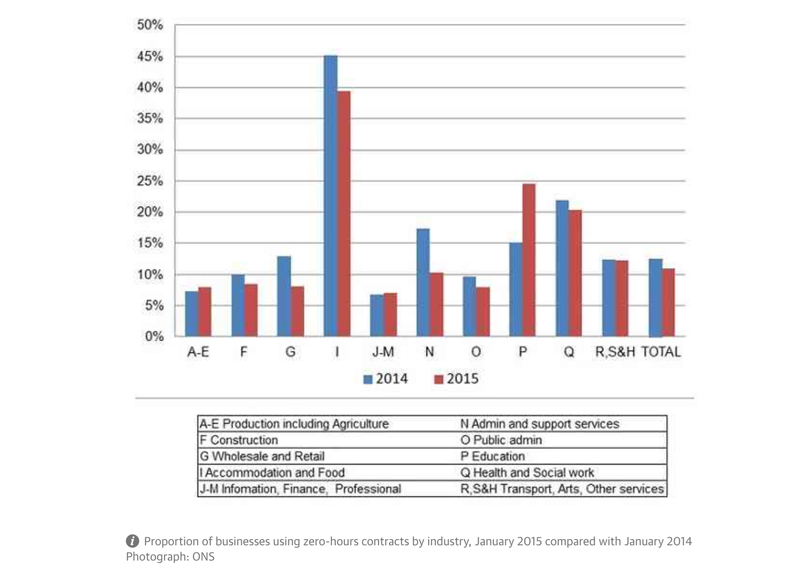

The hotel and restaurant sector is proven to be the largest employer utilizing Zero Hours Contracts, see this interesting debate in The Guardian for background discussion https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/sep/02/number-of-workers-on-zero-hours-contracts-up-by-19

The Office of National Statistics chart (above) shows clearly the extent to which these contracts are prevalent in the industry; a sector that also happens to be one of the largest utilizers of the freedom of movement of labour in the EU (A separate Brexit impact discussion).

The UK National Living Wage was introduced for those over twenty-five years of age, to work in conjunction with the National Minimum Wage. These are the rates as of 1 October 2016. Over 25 years of age becomes the National Living Wage which is set at £7.20 per hour; National Minimum Wage 21 to 24 years is £6.95 per hour, 18 to 21 years is £5.55 per hour, under 18 years of age is £4.00 and an apprentice is £3.40 per hour.

National Minimum Wage rates change every October. National Living Wage rates change every April. If an employee is on a Full Time Employment Contract then the relevant National Minimum Wage or National Living Wage still applies. So if a front of house or chef does 70 hours a week for 4 weeks on a full-time employment contract and their monthly pay slip is less than the 70 x 4 x relevant National Minimum Wage for that period then they have been illegally underpaid. The government website provides a simple process to calculate what an employee should be legally paid as a minimum, which can be found through the link provided. www.gov.uk/am-i-getting-minimum-wage/y/current_payment

It would appear that legally the definition of an apprenticeship is not met by staff training in the kitchen or the front of house www.gov.uk/apprenticeships-guide However, the early years of development remain critical to future longevity in the industry, including the possibility of running a kitchen or being a manager in a hotel at a relatively early age. The thinking is for practical education and training rather than a pure academic-led day release style of apprenticeship – Sue William’s conceived ‘ten out of ten’ programme would be close to the more hands-on type of process www.ten-outof-ten.co.uk, or The Roux Scholarship www.rouxscholarship.co.uk, or The Gold Service Scholarship for front of house professionals www.thegoldservicescholarship.co.uk

An example of staff development training in hospitality (Source: ten-outof-ten.co.uk)

Nowadays company internships are the equivalent of staging in the kitchen or placements in the front of house of a restaurant. Those that have reached the top in the restaurant profession more than likely started working in a top restaurant or kitchen for free, never mind the modern day legalities of the minimum wage.

The top kitchens and dining rooms are a craft, an art, a profession that takes years of tutelage combined with a focused passion and dedication to master. When the leaders are interviewed they started humbly and made significant sacrifices both financially and with their social lives for some considerable time.

The top chefs of the world are always passing on their knowledge to the next generation, many who pass through their kitchen door go on to be leaders in their own right. The challenge is finding a structure that promotes loyalty, development and mutual respect; a system that pays fairly but maintains costs at a level that the restaurant business may sustain onwards into the future, building the talent of tomorrow in a positive atmosphere with a sustainable model that continues to produce consistent first class products today!